The appeal of The Great War in Europe is understanding the shock of those who were currently involved, and did not yet know how it might end.

High Point: Besides the narrative, the photographs, drawings and maps tell a fascinating story of the war’s waste and devastation.

Low Point: The realization that we seem to have learned little about the evils of war.

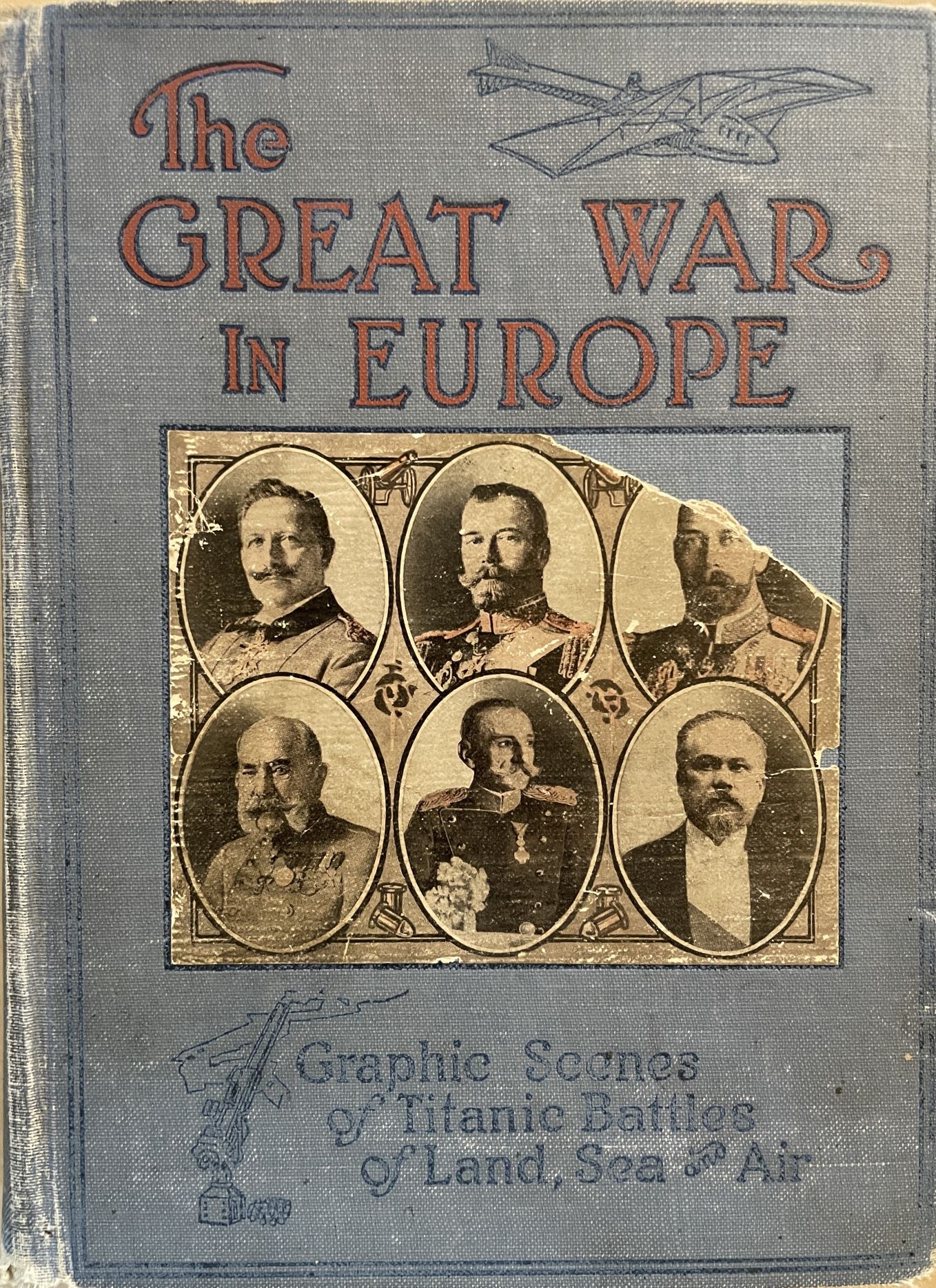

Author: Thomas H. Russell

Publication Date: 1916

Genre: History

Project Gutenberg: Not available

LibriVox: Not available

Movie/TV Adaptation: None

This edition of Thomas H. Russell’s The Great War in Europe was published in 1916—two years after the start of what came to be known as World War I. It would still be another year before the entry of the United States. But the author already recognized that the carnage, suffering and cost would exceed anything experienced in human history.

Cause and Effect

Russell begins by covering the apparent causes of the war by delving into national and racial prejudices and intra-Euro rivalries. Then he relates the trigger event: the assassination of an Austrian Archduke by a young Serb.

Russell provides incredible detail of the ebb and flow of battle after battle; the destruction of cities; and the devastating impact on the civilian population. He concludes his book with US President Wilson’s address to Congress in April 1916 threatening to sever diplomatic ties with Germany.

Russell’s narrative is frequently interspersed with articles from journalists covering the war; reports issued by the military of both sides; letters written by soldiers to their loved ones; and other firsthand accounts. In addition, more than 70 pages of photos, drawings and political cartoons are scattered throughout.

Anger and Dismay

Near the end, Russell includes a poem, “The Day” by Henry Chappell. Chappell was a railway porter in Bath, England. Most likely, he was typical of the common person with his anger at the ungodly violence and grief affecting his everyday life. Chappell’s poem mocks a German military toast— “Der Tag”—and he skewers the aggressors.

Repeatedly, Russell makes it clear that he is dismayed and disheartened by what he sees in Europe. This quote is one of his best, attributed to a war correspondent.

“Before this war, experts used to say perfection of terrible instruments of killing would only tend to make war impossible. It doesn’t do that, though. I watched the Zeppelin dropping bombs upon Antwerp last night, and such perfection only makes war more terrible, with a refinement of barbarism. As I saw the Zeppelin depart it seemed that the best argument against war was that it turned men into such merciless demons as these Zeppelin murderers.”

The appeal of Russell’s The Great War in Europe is the understanding of the shock and disbelief of those who were currently involved in the war, and not yet knowing how it might end.

Quotes

| “Men, the pawns of royal intrigue, have been forced to march to the field of slaughter, accompanied by memory of the weeping of their women and children, and the thought of the misery to fall upon them. A terrible toll of human life and human suffering is being taken in the name of ‘national honor,’ which is often synonymous with the pride of kings or a selfish desire for commercial gain.” |

| “In London, Berlin, Paris, St. Petersburg and Vienna enthusiastic crowds filled the streets, singing national hymns and cheering their respective rulers and popular heroes. Only here and there were thoughtful heads bowed in sorrowful anticipation of coming woe. The residents of the capitals heard only the cheerful sounds of drum and fife. Not yet were their ears assailed by the groans of the wounded and the dying… Not yet had the mournful procession of the myriads of maimed and shattered soldiers begun to wend it slow and painful way back from the front. Not yet had the tears of half a million widows and countless orphans begun to flow… But all this and more were soon to come… Truly, War is Hell—and the workers of the world roast in its fires.” |

| “The greatest of military authorities has made analysis of the history of mankind, showing that in 3,357 years—from 1496 B.C. to 1861 A.D.—there were 227 years of peace and 3.130 years of war, or more than a dozen years of war for every one which was without strife. The peace of Europe has always been a myth.” |

| “Before this war, experts used to say perfection of terrible instruments of killing would only tend to make war impossible. It doesn’t do that, though. I watched the Zeppelin dropping bombs upon Antwerp last night, and such perfection only makes war more terrible, with a refinement of barbarism. As I saw the Zeppelin depart it seemed that the best argument against war was that it turned men into such merciless demons as these Zeppelin murderers.” |